The Great Barrier Reef is one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet, but it is under threat from plastic pollution. Marine plastic pollution is a serious problem that affects the Great Barrier Reef, and it may have originated from anywhere along the east coast. A three-year study of plastic waste in the Great Barrier Reef found a total of 533 synthetic and semi-synthetic plastic items, with microplastics comprising just over half of the total marine debris detected. The impact of microplastics on marine life varies, but if consumed, it can get stuck or clogged within the digestive tract, leading to harmful consequences. The biggest killer of marine life is the plastic bag, as turtles often swallow them whole, causing them to retain air and eventually die. With the amount of plastic pollution in the Great Barrier Reef, collective action by the community, industry, and government is required to address this issue and protect the diverse marine life that inhabits this ecosystem.

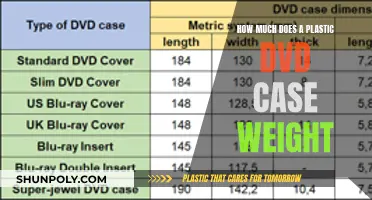

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Percentage of plastic in marine debris found on the Great Barrier Reef | 80% |

| Plastic items found in the central Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area in 2016 | 547 |

| Plastic items found in the gastrointestinal tract of Lemon damselfish | 455 |

| Percentage of microplastics in total marine microdebris detected in surface waters | 56% |

| Percentage of microplastics in total marine microdebris detected in Lemon damselfish | 25% |

| Maximum length of plastic items in surface waters | 55mm |

| Maximum length of plastic items in Lemon damselfish | 13.1mm |

| Estimated yearly input of plastic into aquatic ecosystems by 2030 | 20-53 million metric tonnes |

| Percentage of increase in associated risks in some marine environments by 2030 | 50% |

| Percentage of microplastics in the 533 synthetic and semi-synthetic plastic items found in the Great Barrier Reef | 92% |

| Number of plastic items stuck on coral reefs across the Asia-Pacific | 11.1 billion |

| Percentage of increase in the risk of coral disease in plastic-hit areas | 2000% |

| Number of plastic items stuck on coral reefs across the Asia-Pacific forecasted by 2025 | 15.7 billion |

What You'll Learn

- Microplastics are the most common shape in marine debris

- Plastic pollution affects marine life, including turtles, dugongs, dolphins and seabirds

- Plastic bags in water resemble jellyfish, a turtle's favourite food

- Plastic waste enters the Great Barrier Reef from land systems, such as agriculture and urban settings

- Plastic waste is also carried into the ocean by extreme weather events

Microplastics are the most common shape in marine debris

Plastic is the most common type of marine debris found in our oceans, and plastic debris can come in all shapes and sizes. Microplastics, defined as plastic pieces smaller than 5mm in length, are a particular concern due to their intake by marine organisms. These small plastic pieces or fibres can be so minute that they fit on the tip of a finger or cannot be seen with the naked eye. They are found throughout the ocean, from tropical waters to polar ice, freshwater, and even the air we breathe.

Microplastics come from various sources, including the degradation of larger plastic debris and microbeads, tiny pieces of manufactured polyethylene plastic found in health and beauty products. These microbeads can pass through water filtration systems and end up in the ocean, posing a threat to aquatic life. Microplastics are also produced by our clothing, furniture, and fishing nets, which shed plastic microfibers. These fibres were found at every site in a study of 37 National Park beaches, comprising 97% of the microplastic debris.

In the Great Barrier Reef, microplastics have been detected in both the waters and coral reef fishes, with microfibres of textile origin likely derived from clothing and furnishings. A three-year study found that plastic pollution in the Great Barrier Reef poses a chronic risk to marine organisms, with microplastics being a particular concern due to their intake by marine life. Extreme weather events can also influence microplastic concentrations, with increases in wind speed and river discharges resulting in an outflow of plastic debris from rivers.

The complex transportation and distribution processes of microplastics are influenced by ocean dynamics and their physical characteristics, such as size, shape, and density. Microplastics can act as vectors for pollutants, contributing to the bioaccumulation of toxins in marine ecosystems and potentially impacting human health. They can attract and carry pollutants, as well as release chemicals added to plastics into the surrounding water. While research on microplastics is ongoing, their presence in the Great Barrier Reef and other marine environments highlights the need for long-term monitoring and action to address plastic pollution.

Nylon Plastic Shrinkage: Understanding the Science Behind It

You may want to see also

Plastic pollution affects marine life, including turtles, dugongs, dolphins and seabirds

Plastic pollution is a significant threat to marine life in the Great Barrier Reef, including turtles, dugongs, dolphins, and seabirds. Plastic makes up over 80% of the marine debris found in the Reef and poses a chronic risk to its organisms.

Turtles are one of the oldest living creatures on Earth, with origins dating back at least 110 million years. However, plastic pollution now endangers their future. Mother turtles are forced to lay their eggs on beaches polluted with plastic waste. Newly hatched turtles must navigate through plastic debris to reach the sea, and both young and adult turtles risk entanglement in plastic items, which is often deadly. All seven species of sea turtles ingest plastic, with some populations having more than 90% of individual turtles containing microplastics. The ingestion of plastic has been linked to a one in five chance of premature death, with the risk increasing with the number of plastic pieces consumed. Furthermore, heavy metals and chemicals in plastics have been associated with hormone-disrupting effects, causing feminization and infertility in sea turtles. Microplastics also raise the temperature of the sand on beaches, contributing to the feminization of sea turtle populations as the sex of a sea turtle is determined by the temperature of the sand surrounding its egg.

Dugongs are another species affected by plastic pollution in the Great Barrier Reef. While specific details on the impacts of plastic on dugongs are limited, it is known that they face threats from marine debris, which includes plastic pollution.

Dolphins in the Great Barrier Reef also face risks due to plastic pollution. While specific information on the effects of plastic on dolphins in the region is scarce, it is clear that plastic pollution in the Reef's waters poses a danger to these marine mammals.

Seabirds are impacted by plastic pollution, as they inadvertently feed their chicks pieces of plastic they mistake for food. An Australian shearwater chick was found to have over 80 pieces of plastic in its stomach, leaving no room for nutritious food. As plastic breaks down into smaller pieces, they are more easily consumed by marine life, including seabirds, and can absorb and accumulate toxins and heavy metals. These toxins are then passed up the food chain, eventually reaching humans.

Collective action is required to address the plastic pollution affecting the Great Barrier Reef and its marine life. This includes the reduction of single-use plastics, such as straws and plastic bags, and the promotion of recycling and sustainable practices by individuals, communities, industries, and governments.

The Heavy Cost of Plastic: Tonnes and Dollars

You may want to see also

Plastic bags in water resemble jellyfish, a turtle's favourite food

Plastic pollution is a serious problem for the Great Barrier Reef, and it is not restricted by state boundaries. A three-year study of plastic waste in the area found there is a chronic risk to marine life from plastic exposure.

One of the most affected species is the sea turtle. Turtles are highly susceptible to confusing plastic bags with jellyfish, one of their primary food sources. Floating plastic bags can look deceptively similar to jellyfish, and sea turtles use their sense of sight to locate and track their prey. Semi-opaque white plastic bags, in particular, bear a striking resemblance to jellyfish when floating in the water. When microbes, algae, plants, and tiny animals start to colonise the plastic bags, they also smell like food to turtles.

The consequences of this confusion are dire. Turtles often swallow plastic bags whole, retaining any air that's trapped inside. This extra buoyancy means turtles cannot dive for food, leading to starvation. The ingestion of plastic can also make turtles unnaturally buoyant, which can stunt their growth and lead to slow reproduction rates. In some cases, sharp plastics can rupture their internal organs, causing internal bleeding and death. Even if they survive ingestion, consuming plastic negatively impacts their growth, buoyancy, and reproduction rates.

Research suggests that 52% of the world's turtles have eaten plastic waste. Turtles can also get entangled in plastic debris, abandoned fishing nets, six-pack rings, and other plastic waste, which can choke, injure, or drown them. Baby turtles are especially vulnerable to plastic entanglement, as it can prevent them from reaching the sea.

Mexico's Plastic Pollution: A Watery Grave

You may want to see also

Plastic waste enters the Great Barrier Reef from land systems, such as agriculture and urban settings

The Great Barrier Reef, located off the coast of Queensland, Australia, is the largest coral reef ecosystem on Earth and a UNESCO World Heritage Area. However, it is under threat from plastic pollution, with billions of pieces of plastic waste, including microplastics, littering its waters. This plastic pollution comes from a variety of sources, including land-based systems such as agriculture and urban settings.

Agriculture

Unsustainable farming practices, such as the use of nitrogen-based fertilizers, can have detrimental effects on the environment and people. In the case of the Great Barrier Reef, farm pollution from nearby sugarcane farms has contributed to the degradation of the reef. Nitrogen run-off from fertilizers can enter waterways and promote the growth of Crown of Thorns starfish, which damage coral tissue and lead to reef deterioration. To address this issue, organizations like WWF-Australia and The Coca-Cola Foundation have partnered with farmers and the Australian government to implement more sustainable practices that reduce environmental impact while enhancing crop production. These efforts have already shown significant results, with a notable reduction in pollutant loads and improved water quality, benefiting the fragile coral ecosystem.

Urban Settings

Urban areas also contribute to plastic waste entering the Great Barrier Reef. A three-year study of plastic waste in the central Great Barrier Reef found that microplastics, particularly microfibres of textile origin, are a significant concern. These microplastics are often derived from clothing and furnishings, ending up in the ocean through river discharges and extreme weather events. The study emphasized the need for long-term monitoring of the marine environment to address the chronic risks of plastic exposure to marine organisms. Additionally, urban settings contribute to food waste, which, when sent to landfills, produces methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Composting food scraps can help reduce emissions and mitigate climate change, benefiting the Great Barrier Reef and the planet.

The Ocean's Plastic Problem: Where Does It Come From?

You may want to see also

Plastic waste is also carried into the ocean by extreme weather events

Plastic waste is carried into the ocean by rivers, which act as arteries transporting plastic from the land to the sea. Extreme weather events, such as storms, heavy rainfall, typhoons, and floods, can cause plastic emissions to increase significantly. During these events, trash is washed into waterways, with rivers being a primary conduit. While not all plastic in a river will reach the ocean, the likelihood of this increases with proximity to the coast.

The impact of extreme weather events on the distribution of plastic waste in the ocean is significant. Heavy rainfall and flooding can scour and reorganize microplastics in riverbed sediments, with a single flood event capable of carrying away up to 70% of the microplastics loading on the riverbed. Storms and heavy rain events can increase plastic emissions by up to tenfold, contributing to the plastic pollution in the ocean.

The fragmentation of plastic into microplastics during extreme weather events poses an even greater threat to the ecosystem and human society. Microplastics, due to their smaller size, can be carried further distances and serve as efficient pollutant vectors. They may also bioaccumulate along the food chain, impacting marine life and potentially entering the human food system.

The Great Barrier Reef, a delicate marine ecosystem, is particularly vulnerable to plastic pollution, including the microplastics that are prevalent in the area. A three-year study found that microplastic concentrations in the reef were significantly influenced by extreme weather events, with increases in wind speed and river discharges leading to an outflow of plastic debris from rivers. The study also concluded that the overall trend of plastic contamination did not change over the three years, indicating a chronic risk of plastic exposure to marine organisms in the Great Barrier Reef.

Blow Molding: Biodegradable Plastic's Cost and Environmental Benefits

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It is difficult to give an exact number, but a three-year study of plastic waste in the Great Barrier Reef found a total of 533 synthetic and semi-synthetic plastic items. Plastic makes up more than 80% of the marine debris found on the Reef.

Plastic pollution that affects the Great Barrier Reef may have originated from anywhere along the east coast. Plastic enters the ocean from land systems such as agriculture, urban settings, stormwater drains, and debris washing out into the ocean. Extreme weather events can also increase the amount of plastic in the ocean.

Plastic pollution poses a significant threat to marine life on the Great Barrier Reef, including turtles, dugongs, dolphins, and seabirds. Plastic can cause coral reefs to become stressed through light deprivation, toxin release, and anoxia, increasing the risk of coral disease. Microplastics, in particular, can be ingested by marine organisms, causing unknown biological impacts.